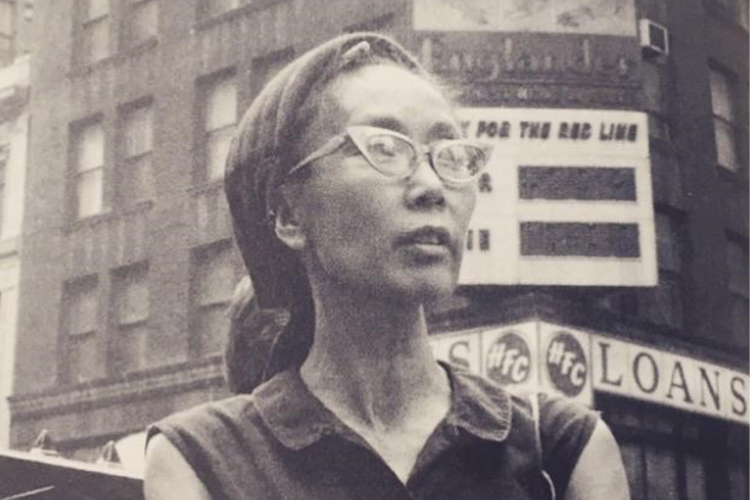

Amongst these 125,000 Japanese Americans was Yuri Kochiyama; a 20 year old at the time, her family's internment and father's death would prompt her to become a social activist until her death in 2014. Under Executive Order 9066, the Kochiyama family was subjected to internment and detained Yuri's father, Seiichi, due to suspicion. Seiichi, who was recovering from surgery and in poor health, died soon thereafter. The rest of the Kochiyama family was relocated from their house in San Pedro, California, to a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas, for two years. Having undergone governmental abuse, Kochiyama was inspired to continue fighting for civil rights even after the order was revoked in 1945. After moving to Harlem in 1860 with her husband, Bill Kochiyama, where she hosted community meetings and invited speakers like the Freedom Riders. She participated in the Asian American, Black, and Third World movements against the war in Vietnam. Each new decade prompted a new wave of activism for her, where she got involved with civil rights movements for a variety of racial groups, prompting intersectionality. In 1963, she met Malcom X, joined his Organization for Afro-American Unity, and was a close friend of his until he was fatally shot in 1965. In the Life Magazine Article "Death of Malcolm X," she can be seen crouched in the background cradling his head after the shooting. In the 1970s, she joined Puerto Rican nationalists when they occupied the Statue of Liberty in 1977. She also joined Asian Amercians for Action, and in the 80s, she was active in the Redress movement that sought reparations from the American government for the unconstitutional incarceration of innocent Japanese Americans. She fought for individual convicts she believed were wrongfully convicted, such as Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Black man; Marilyn Buck, a white female anti-war poet; and David Wong, a Chinese Immigrant. Kochiyama visited Wong, who was falsely sentenced to life in prison in 1987 on a charge of murder, in prison and helped start the David Wong Support Committee, which eventually helped overturn his conviction in 2004. In the 90s, Kochiyama continued to fight by speaking out against the increasing Islamophobia following the Persian Gulf War, and after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Kochiyama spent her life fighting for intersectional causes that have left a remaining mark on U.S. laws and history.

Conditions in the Japanese Internment Camps were terrible: the army-style barracks offered little protection from weather conditions and families were often forced to live together. Most families were relocated there solely on the basis of their Japanese ancestry and were innocent American citizens. Despite these restrictions, incarcerated Japanese Americans established newspapers, schools, markets, and police/fire departments to offer a sense of a home. In 1943, the War Relocation Authority subjected all Japanese Americans in camps to a loyalty test – they had to reject allegiance to the Japanese Emperor and assert whether they were willing to serve the U.S. military. Many Japanese Americans, some of which were American citizens, were offended by these accusations of disloyalty and answered "no" to both questions in protest. About 8,500 Japanese, mainly nisei men, replied "no," were labelled as disloyal, and were relocated to Tule Lake, California. This separation further shows the illogical basis of the incarceration — if the government had separated the "loyal" and "disloyal" Japanese Americans, they had no legal reason to continue detaining the loyal subjects. Arguments like these were taken to the Supreme court in the 70's and 80's during the Redress movement, a movement that fought for reparations (monetary compensation and/or a formal apology from the government) for incarcerated Japanese Amerians. From 1987, when the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) founded the Redress Committee, it took years for the movement to become legislation. The committee opened up reevaluation of the constitutionality of the Executive Order 9066 through the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens (CWRIC), signed by President Carter in 1980. After efforts by the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR) and the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR), on February 24, 1983, the CWRIC issued its report Personal Justice Denied. It concluded that Executive Order 9066 was ""was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—detention, ending detention and ending exclusion—were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria, and failure of political leadership." The Redress movement was successful, and in 1988, the Civil Liberties Act issued a formal apology from President Reagan and gave $20,000 to all Japanese Americans that survived incarceration.