If one day, you woke up and were forced to move thousands of miles away from your home in less than a week, how would you feel? Now imagine it's not just you — more than 125,000 other people are moving alongside you with a similar situation.

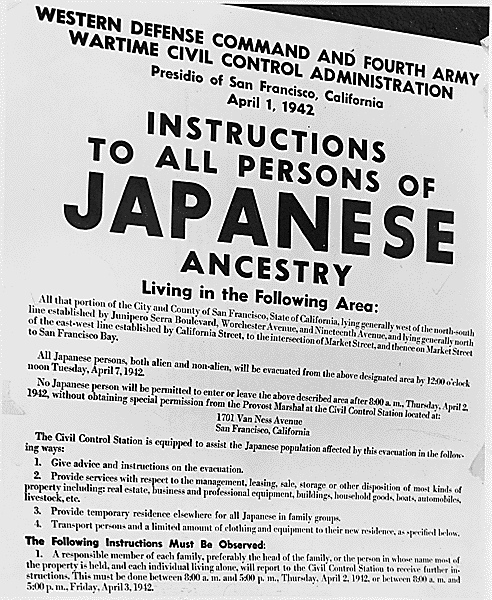

Unfortunately, for most Japanese American families in the 1940s, this imaginary situation was their brutal reality. Prompted by the Empire of Japan's attack on the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii and motivated by Anti-Asian racist sentiment, on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 that allowed the internment of Japanese Americans. The U.S. government claimed that Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security, and that there was not enough time to differentiate between those who were loyal and unloyal to the American government. Thus, this executive order on February 19, 1942, allowed the relocation of Japanese Americans to the West, causing over 125,000 issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) and nisei (second-generation Japanese immigrants) to be forcibly moved from their homes to internment camps. The laws under Executive Order 9066 became known as the Japanese Exclusion Acts, which included proclamations like Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt's Public Proclamation No. 4. The proclamation began the forced evacuation of and detention of Japanese American West Coast residents on a 48-hour notice. Days later, Congress passed Public Law 503, which made violation of Executive Order 9066 punishable by up to one year in prison and a $5,000 fine. Targeting issei and nisei alike, the Japanese Exclusion Acts were a racially motivated unconstitutional order that affected Japanese Americans – even those who had citizenship – and prompted years of harsh conditions in internment until the order was revoked in 1945.